Jane Austen died on July 18, 1817 at the age of 41.

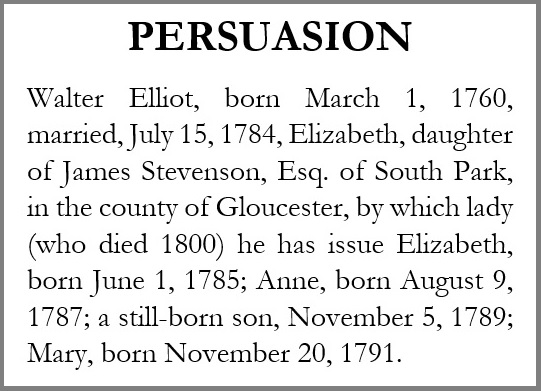

Death lurks on the pages of her Regency era novels — Persuasion, for example, would have been a different story had Lady Elliot and/or her son survived — but it stays in the background, playing a relatively minor role considering the morbid reality of the time. According to Austen scholar Fiona Stafford, as quoted from Jane Austen: A Brief Life in the New York Times (In Jane Austen’s Pages, Death Has No Dominion by Radhika Jones):

By 1817, [Austen] had seen the lives of two first cousins, three sisters-in-law, her sister’s fiancé and her cousin’s husband all cut short. She had lost her father and mourned the deaths of aunts and friends. Her letters are scattered with references to stillbirths and miscarriages, to mothers who died in labor and to infants who succumbed soon afterwards.

Two hundred years ago, average life expectancy in England and Wales was only around age 36 or 37. See Robert Wood, The Effects of Population Redistribution on the Level of Mortality in Nineteenth-Century England and Wales (1985). I don’t know what the average life expectancy was for women of Jane Austen’s socioeconomic class in her region, but I think it’s fair to say that her lifespan of 41 years was hardly unusual for the time.

However, there is evidence to suggest that Austen’s genes and environment held the potential for longevity. As Oxford professor Helena Kelly notes in Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, Austen’s father lived into his 70s, her mother lived to 87, her sister Cassandra lived to 72, and her brother Frank lived to 91, a ripe old age even by our modern standards.

In her book, Kelly describes the day Austen died, writing in Chapter 8:

Dr. Lyford was sent for. He “applied something to give her ease” –almost certainly a substantial dose of laudanum…

At half past four in the morning of Friday, July 18, she died.

She was, it’s fairly clear, killed with kindness. A dose of opiates strong enough to knock her out completely for nine hours has to have at least hastened her death… We may have to consider the—frankly horrifying—possibility that Jane’s illness wouldn’t, on its own, have proved fatal, or not so soon, that it might have been the drugs, and only the drugs, that killed her.

I’ve read a number of theories about the cause of Austen’s death, including Addison’s disease, tuberculosis, lymphoma, and arsenic poisoning, but this portrayal of Austen’s doctor as an “angel of death” is new to me.

It’s plausible that Austen’s medical treatment could have hastened her death — after all that still happens today, resulting in lawsuits like the one against a medical device company at the heart of Amelia Elkins Elkins (a modern take on Persuasion) — but I wouldn’t say it’s “fairly clear,” as Kelly does. Austen’s health had been in decline before she received her final dose of Dr. Lyford’s medication.

Whatever the cause of Austen’s death, whether premature by the standards of her time or not, it’s too bad she didn’t live longer. We can only imagine what else she would’ve contributed to our literary world. As Geoff at The Oddness of Moving Things writes:

I mean she was writing a book, Sandition, near her death with a MIXED RACE character. How would she have finished it? How would it have been accepted? Kelly showed how saucy (to use Austen’s own words) Austen was, how far would she have taken it if she wrote for another 10, 20, 30 or even 40 years?

I wish we knew.

Up till now,I never gave this much thought to Austin’s death.I only celebrated her work.

The possibility of having 40 more years of Austen’s writing, but not having them, is too depressing! Also an interesting idea though 🙂

I have not heard this thesis about Austen’s death before. I suppose it’s possible. Even if it is true she was ill, as you say, so there is no telling how much longer she would have lived and whether she would have been able to write. I do like to hear all the speculation even though we will never know for sure.

I like hearing the speculation too, even though I’m skeptical. Kelly’s theory is definitely an interesting one with many modern parallels.

My first thought upon finishing reading this post was of the title of a Kurt Vonnegut novel: God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian.

That came to mind for me too!

This was an interesting read, my interest is piqued and I will read more on Jane Austen

I’m glad you found it interesting! Thanks for stopping by.

I wish so too! This was very interesting. Thanks!

I’m glad you found it interesting. Thanks for stopping by!

I wonder what Jane would’ve thought about the attention on her death 200 years later!

Who knows! I bet she’d be pretty surprised by her fame in general.

Thanks for the shout out! I’m actually in mourning today 😦

It was my pleasure to quote your thoughts on Austen and your review of Kelly’s book. Kelly makes some interesting arguments, but I wasn’t particularly impressed by her supporting evidence (such as in the laudanum example. It’s plausible, but not fully convincing).